Ebru Art - Meeting Artist Hayrettin Kozanoglu

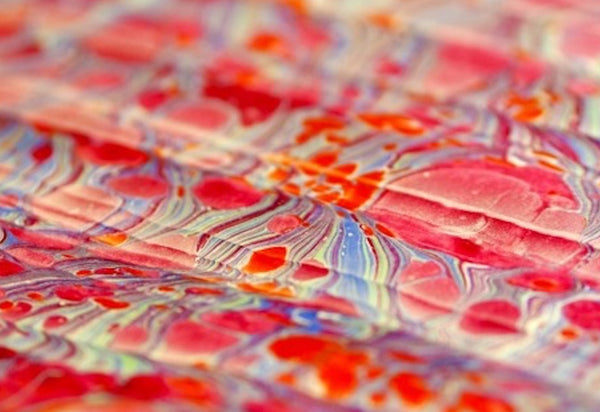

Deep red droplets fall from a wooden brush made of rosewood and natural horse hair. The droplets spread rapidly as they hit the water, creating huge circles that glide across the metal tray. Within seconds, the intense red hue has disappeared - the pigment particles have spread so thinly, they appear to have lost their most fundamental essence - colour.

A bright turquoise paint is dropped into the tray. The turquoise paint spreads but maintains its colour and intensity. The new occupant of the tray forces the dense, red to reappear, but only as thin streaks and fissures in a sea of turquoise.

I am in a brightly lit studio in North London, with artist, Hayrettin Kozanoglu. Every available surface seems to have been covered with newspaper, in preparation for the fresh designs that will be lifted from the water. Heaters have been placed around the room and it is uncomfortably hot. The heat accentuates the pungent smell of ox gall - the digestive juice of cattle - which is mixed into the paints, to alter their physical properties and allow them to spread. Hayrettin turns a heater off for me and politely explains that the room must be kept warm for the paints. Over the course of the next few weeks, I will learn more about the water, the paints and their very specific needs and requirements.

Ebru, a form of painting on water, has been practised in Turkey for over 500 years, having arrived there from the Far East. Generation after generation of Sufi masters developed and passed down this spiritual and mystical art form, supported and promoted by wealthy Ottoman rulers. As with other Islamic art forms, Ebru artists sought spiritual awareness and inner knowledge, through the outward expression of physical beauty.

Hayrettin has been studying and practising Ebru for eight years. He has learned and developed his technique under Ebru masters in Turkey, but much of his knowledge is self taught. Quietly spoken, he exudes a calm demeanour which seems fitting for such a tranquil art form.

As Hayrettin produces pattern after pattern, he explains the processes involved in preparing the elements of Ebru. The watery canvas - called the ‘size’ - is a gel-like mixture of water and carageen - seaweed extract - which has to be prepared at least a day prior to painting. At room temperature, it will only last a day or two, before starting to degrade. This watery ‘size’ gives body and thickness to the water and prevent the paints from sinking to the bottom of the tray. As Hayrettin does not have running water in his studio, he carries the prepared solution up several flights of stairs before each session.

I feel humbled by the effort required just to produce the canvas, but this is only one part of the preparation. The pigments used in traditional Ebru are derived from natural sources - indigo from the Indigofera plant, Indian red, an iron oxide extracted from the earth, and ultramarine from crushed lapis lazuli gemstones. Once in powdered form, the pigments are crushed by hand, between blocks of marble and water is added to create a creamy consistency.

Hayrettin sources the finest, natural pigments from Turkey. They have already been crushed, but there is still more work to do before the paints can be used. Ox gall is mixed into the paint to weaken the physical bonds between the particles. With this reduced surface tension, the paints spread in the blink of an eye and appear to defy their own, natural limits - this is what makes Ebru so hypnotic to watch. The pigment particles do not dissolve in water. They remain suspended as tiny solids. If the natural earth sources are impure, if they are not crushed adequately or if the ox gall is not added in precise amounts, the particles will not spread on the surface of the gel mixture. Instead, they will sink and remain suspended in the lower layers of the gel. The training and experience of the artist is key to understanding the correct balance and time required to prepare the paint and ox gall mixture.

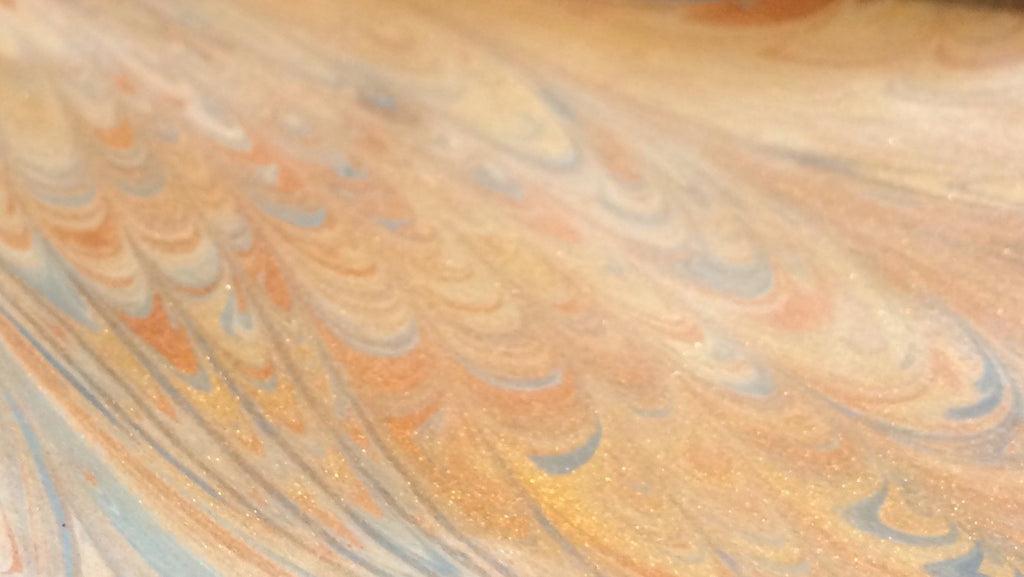

After such a long process of preparation, the painting process itself is surprisingly quick. Hayrettin adds colour after colour, completing an entire painting in just a few minutes. He works fast, as the paints will not slow down or pause for him to consider his next colour choice. Unlike working on paper or canvas, he cannot place a colour exactly where he wants to and he cannot take time to build up shades of colour. With many years of experience, it is clear that he is familiar with the character of his paints - he knows which colours are strong enough to overpower the others, which ones will end up as thin crackled lines and fractures and how the intensity of the colours will change, based on the density of the pigment and surface tension of the paint.

The process is mesmerising to watch. The final designs are beautiful, but it’s the movement and dynamism of the paint, the feeling that the paints are alive, that really draws you in and makes it so difficult to look away. Watching the creation of the designs, understanding the various elements that must be perfectly prepared to allow just those few minutes of painting, creates a sense of awe and respect, over and above the aesthetic beauty of the final print.

When all colours have been added, a single sheet of paper is added to the tray. The paints, sitting on top of the size, transfer themselves to the paper, leaving minimal residue in the tray. Hayrettin lifts the print off the tray and leaves it on the newspaper to dry. The paints are so much brighter on paper, than in the murky, metal tray, that the final print, lifted from the tray, always comes as surprise. As the paper dries, the colours change once more and the pigments, which may have originated from a quarry in Italy, a plantation in India or from the highlands of Peru, finally come to a rest.